A Short History of the Trombone

The Wind Band and Popular Orchestra Traditions

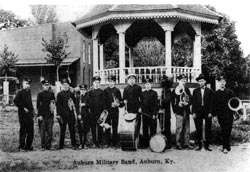

Auburn (KY) Military Band c. 1915-1920 |

(5.1) The first wind bands were three piece Alta Bands(1.6) of shawms and slide trumpets. Eventually, the standard instrumentation changed to cornetts and trombones. In the late seventeenth century, the French court changed their standard wind band instrumentation to oboes and bassoons. Most other courts throughout Europe soon followed suit. The clarinet and horn joined this group by the middle of the eighteenth century, and pairs of these four instruments became not only the standard wind band but also the standard wind component of the symphony orchestra.

(5.2) The French Revolution sought to overthrow not only the monarchy, but the entire class system it was based on. Almost overnight, French music radically changed in character. Among the more conspicuous changes was the development of an unprecedented wind band. The new republican government mandated major festivals every year to commemorate Bastille Day and other key events of the Revolution. These festivals customarily took place out doors.

(5.3) A string orchestra, besides having aristocratic connotations, could not stay in tune or produce enough sound. The standard eight-piece wind band (pairs of oboes, clarinets, horns, and bassoons) was likewise too reminiscent of the monarchy and not loud enough for outdoor events that drew large crowds. And so the government settled on a wind band the size of an orchestra. It consisted both of a greater than usual number of the normal instruments and the addition of instruments, including three trombones, that had not been used in military music before. A few of the compositions written for this band, notably François-Joseph Gossec's "Marche lugubre," are still performed occasionally today.

(5.4) Because Napoleon was little interested in music, he allowed military music to wither away. The chief exception was the cavalry band, which was expanded to include sixteen trumpets, six horns, and three trombones. Such an ensemble could give much more sophisticated signals to the troops. It also produced perhaps the most brilliant sound heard since the glory days of St. Mark's cathedral in Venice. It had imitators wherever it was heard.

(5.5) In the nineteenth century, the most innovative program of military music was in Prussia, where Wilhelm Wieprecht introduced valved instruments and standardized the instrumentation of the band. Once his plan was firmly established, the typical infantry band had four trombones and the typical cavalry band three.

(5.6) The modern march originated in Austria. Important composers include Johann Strauss, Sr. and Julius Fucik. Although bands in the non-German speaking parts of Europe were less innovative than the Germans and Austrians, there were lots of bands all over the world and an impressive body of music, most of which is now found only in various archives. It includes both original compositions (mostly marches and dance music) and transcriptions of operatic and symphonic literature.

(5.7) Although there were many civilian bands modeled on the military bands, the English brass band was unique in devising its own traditions. Its instrumentation was standardized some time in the 1850s, based on cornets, saxhorns, and tubas. Trombones are the only cylindrical-bore instruments in a brass band.

(5.8) Both of these kinds of band were amateur bands, the first time in history that significant numbers of amateurs played trombone, or virtually any other wind instrument. Part of the reason for the proliferation of amateur musicians is that the working classes had leisure time and disposable income for the first time in history, and the ruling classes thought that music was a politically safe outlet for their energy.

(5.9) In the United States, all-brass bands began to form in the 1830s and all but supplanted mixed woodwind and brass bands by the time of the civil war. Patrick Gilmore, however, formed a professional touring band with mixed instrumentation, which became so successful that the various brass bands began to admit woodwinds. Among the many excellent soloists that performed reguarly with Gilmore's band was trombonist Frederick Neil Innes. After Gilmore's death, John Philip Sousa formed another very successful band, with soloists that included trombonist Arthur Pryor. Pryor, Innes, and many others formed their own bands after the beginning of the twentieth century.

(5.10) One reason why the United States could support so many professional bands is that there were literally thousands of amateur bands. In the days before movies, radio, and television, every town of any size had at least one band. Businesses and civic organizations often sponsored bands. Many of these bands were led by trained professional band masters, but many more were not. What they lacked in skill and training, they made up in enthusiasm. Besides providing an audience for touring professional bands, the abundance of amateur musicians helped create a market for band music and band instruments.

(5.11) The Great Depression, which began in 1929, made it financially impossible to maintain such large bands. When it was over, popular music had gone in another direction. But if professional bands are now uncommon, there are many school bands, college bands, community bands, and military bands. In about the last quarter of the twentieth century, a new vogue for British-style brass bands began in the United States.

(5.12) Popular orchestras, which were mostly dance orchestras rather than concert organizations, have attracted relatively little scholarly attention, but they are important in the history of the trombone. The first composer to use trombones to play the melody was apparently Philippe Musard, leader of a dance orchestra in Paris. Antoine Dieppo, trombone professor at the Paris Conservatory played solo trombone in Musard's orchestra. Joseph Lanner and the Strauss family in Vienna led similar orchestras, as did Louis Jullien in London. Felippe Cioffi was one of Jullien's solo trombonists. In addition to dance halls, orchestras of this kind provided music for various pleasure gardens during the summer. Leipzig trombonist Carl Traugott Queisser owned and operated such a garden and performed there regularly. Cioffi appeared regularly at Niblo's Garden when he was in New York. In these settings they played arrangements of popular songs and operatic excerpts, among other lighter fare.

(5.13) There are still plenty of bands, but there are no longer orchestras of this type, although several symphony orchestras sponsor "pops" orchestras or present "pops" concerts that feature some of the same kinds of music. Trombones continue to play dance music into the twenty-first century, but much of it comes broadly under the heading of jazz (7.3).

The Wind Band and Popular Orchestra Traditions: Reading list

Carse, Adam. The Life of Jullien. Cambridge, England: W. Heffer & Sons, 1951.

Guion, David M. "Felippe Cioffi: A Trombonist in Antebellum America". American Music 14 (1996): pp. 1-41.

Guion, David M. The Trombone: Its History and Music, 1697-1811. New York and London: Gordon and Breach, 1988.

Hazen, Margaret Hindel, and Robert M. Hazen. The Music Men: An Illustrated History of Brass Bands in America, 1800-1920. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonion Institution, 1987.

Instrumentalist. Numerous articles.

Journal of Band Research. Numerous articles.

Newsom, Roy. Brass Roots: A Hundred Years of Brass Bands and Their Music. Aldershot, Hants, England: and Brookfield, Vt.: Ashgate, 1998.

Whitwell, David. Band Music of the French Revolution. Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1979.

Whitwell, David. The History and Literature of the Wind Band and Wind Ensemble. Vol. 5, The Nineteenth Century Wind Band and Wind Ensemble in Western Europe. Northridge, Cal.: Winds, 1984.