A Field of Scarecrows: A Review

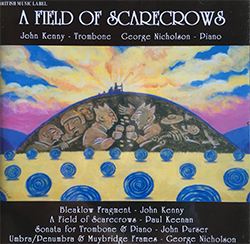

A Field of Scarecrows. John Kenny, trombone; George Nicholson, piano. 2003 British Music Label. 74 minutes. Sonata for Trombone & Piano, John Purser; Scarecrows Improvisation No. 2, Paul Keenan; Umbra/Penumbra, George Nicholson; A Field of Scarecrows, Paul Keenan; Breaklow Fragment, John Kenny; Muybridge Frames, George Nicholson.

A Field of Scarecrows. John Kenny, trombone; George Nicholson, piano. 2003 British Music Label. 74 minutes. Sonata for Trombone & Piano, John Purser; Scarecrows Improvisation No. 2, Paul Keenan; Umbra/Penumbra, George Nicholson; A Field of Scarecrows, Paul Keenan; Breaklow Fragment, John Kenny; Muybridge Frames, George Nicholson.

As a former trombonist whose professional life now focuses on helping artists make a difference in the world and helping those who want to make a difference in the world become more creative, I do not often enough take the opportunity to write about the craft of playing the instrument I devoted the first 25-years of my career to. So, I hope you will forgive me if these words veer toward exploring art's ability to connect more deeply with the human experience, rather than an examination of the trombonist's technical prowess, expansion of the canon, or command of extended techniques: all of which John Kenny has conquered over and again during his historical career. And although I have missed the concentrated focus of striving for mastery (or perhaps simply wrangling the instrument), I have valued the time to reflect upon this question:

How might embracing the joy of the struggle serve us as a path for becoming an artist to the world?

Art and artists by definition tell stories that have not yet been told and create moments that express universal truths about the human condition. And by doing so, and this is the great mystery of art, deepen our empathy for one another.

Take a moment. Think about the artist, regardless of genre or time period, that moves you most: the artist whose music connects you more deeply to that which makes you fully human.

The two things of which I am certain will be true of every reader's choice is, that 1) their artist has a one-of-a-kind voice, and that 2) they have a story. We all have a story.

Consider a moment when you felt consumed by art. Immersed in its power and beauty and message. These artistic moments - the undeniable, inseparable connection of art, artist, and audience - allow us to more fully access our humanity, and to one another's.

Some of my earliest artistic epiphanies happened as a teenager when listening to the mournful weep of Miles Davis' horn. Absorbing Davis' quintessential use of the Harmon mute as a means for shaping his sound. Coming to grips with the depth of his decision to embrace of the countless pitches that fall between the twelve that historically shackle lesser musicians.

Despite the thousands of trumpeters who have recorded over the past century, consider the magnitude that listeners with even a cursory familiarity with Davis' one-of-a-kind sound will instantly and intimately recognize his spiritual cry, his honest expression of the human condition.

Or how graffiti artist JR is capable of unpacking a broad range of contemporary societal issues that span the politics of migrant life during a period of rising nationalism to the complexities of a decades-old conflict. And how, through art, simply seeing each other Face 2 Face might serve as a remedy to violence.

What Davis and JR share reveals that which connects all artists: an ability to disentangle our most complex and personal emotions, speak to our universal humanity, create moments that help us heal, speak to the larger issues that face a world in need, and allow us to feel more connected to another person.

Defined by his creativity (not simply re-creativity) and his signature composer-performer collaborations, Kenny is among trombone rarity: a performer who has both established himself as a master of the instrument, as well as one who warrants artist distinction.

A Field of Scarecrows (British Music Label, 2003) solidifies, proof positive, John Kenny's place among trombone-elite. This well-earned status is encapsulated within the opening bars of John Purser's "Sonata for Trombone and Piano." Kenny's treatment of the trombone's lyrical counterpoint in juxtaposition with the piano's more angular ground reveals a deep understanding of his instrument's centuries-long history with the human voice.

In George Nicholson's "Muybridge Frames," Kenny launches into a more than 22-minute dialogue with composer-as-pianist that spans the range of the instrument. Amidst Kenny's fragmented conversation, he generates an intensity that is only made possible as a result of his seemingly inexhaustible endurance. This recording alone suffices for Kenny to claim the mantle of trombonist-tour de force. But it is Kenny's collaborations with composers - collaborations that most often position him as co-creator, rather than simply performer - that reveal the artist within him.

Kenny achieves this rarified status, in part, by his ability to influence composers' approaches to their craft when writing for him. This is well documented within his longstanding relationship with Paul Keenan. Although atypical of his compositional vocabulary, when writing "A Field of Scarecrows" (the work after which this album is titled) for Kenny, Keenan was persuaded to include a generous stretch of free-improvisation. In Kenny's words, this allowed "the two performers time to consider, to reflect and distill the implications of the piece in which they are immersed, and to make a personal response to that moment in time."

The improvisation, while embedded within the arc of the nearly 24-minute work, finds fertile ground amidst a harmonically complex, melodically angular exchange among piano, trombone, and orator. This too, lends itself to moments of virtuosity, showcasing Kenny's command over the instrument. Further evidence of the composer's willingness to give way to Kenny's relentless creativity can be found in Keenan's willingness to include an outtake of the free-improvisation on the album. "Scarecrows" - a 1-minute 45-second improvisation - reveals Kenny's creative genius, as he slides between extended techniques, musical languages, the introspective and the outrageous, all whilst in intimate dialogue with his collaborative pianist.

Warmly recalling his creative interplay with Keenan during the compositional process, Kenny muses, "imagine the ear as a camera, snapping each fraction of present time as you travel." This breathtaking quote captures the depth and breadth of their collaboration: Before Keenan turns the key that starts the engine of his auditory motorbike, he makes the decision to not only invite the performer to come along for the ride, but to help map the journey. It is in this moment that "A Field of Scarecrows" unveils a rarified collaboration of spirit: a true composer-performer exploration, travelled in tandem.

Kenny's curiosities and collaborative spirit, however, goes beyond the strictly compositional, extending to life's bigger questions, including, and perhaps most importantly, art's ability to connect us to another person. This is embodied within another Kenny composer-performer collaboration: his engagement with George Nicholson.

Composed for Kenny in 2002, "Umbra/Penumbra" explores the sense of loss and grief experienced in the wake of Paul Keenan's death a year earlier. Nicholson takes good advantage of Kenny's comprehensive command of extended techniques (including circular breathing and multi-phonics) to explore expressive possibilities between pitches. Here, it is Kenny's virtuosity that allows him to create meaning out of madness, make sense of the senseless: the death of his friend.

Full circle: How might embracing the joy of the struggle serve us as a path for becoming an artist to the world?

More than rendering a work that demands a vast technical command of the instrument and more than revealing a composer's artistic intentions, artists are charged with creating new meaning, offering a one-of-a-kind perspective of the human experience and sharing their unique vantage point with others as a way of helping making sense of the world.

"Bleaklow Fragment" - Kenny's 2002 requiem to Keenan - depicts a shared moment between Kenny and Keenan. While hiking what Derbyshire locals consider to be among the most dangerous trails within the National Trust's High Peak District, a shift in weather and drop in visibility made the path nearly impossible to navigate. What was planned to be a carefree day of adventure quickly became a moment of uncertainty and fear.

Stark piano fragments and haunting muted trombone melodies open the 4-minute 9-second work. An early morning voyage begins. Kenny's soaring lines traverse the range of the instrument, reflecting the vast terrain he and Keenan would travel together during the notorious climb. Trombonist and pianist toggle between moments of unison and divergence as paths entwine and diverge. Above all, what can be heard in the interweaving's of "Bleaklow Fragment" are echoes of Kenny's concern for the safety of his friend and creative companion, Paul Keenan.

Both composer and collaborator survived the hike. And Kenny, as a reminder of the harrowing experience, took a trophy: "a shard of something ancient, rugged, glistening mica - not as a talisman, but as a reminder of a sense of 'rightness,' which seemed to contain an important personal truth. It was a reminder of friendship."

A Field of Scarecrows achieves everything an artist sets-out to accomplish when releasing a new recording. The album introduces new repertoire for solo trombone that is both evocative and substantial. The recording, underpinned by a technical prowess that few can claim, cements Kenny's position as a leading performer of new music. But indeed it does something more. Fueled by a desire for human connection and driven by a relentless commitment to discovering the one-of-a-kind artist within, A Field of Scarecrows establishes John Kenny as something more than an artist-to-a-panel of his peers, but an artist to the world.

This and many other recordings are available at http://carnyx.org.uk.

|

Sonata for Trombone and Piano, John Purser |

Scarecrows Improvisation No. 2, Keenan, Kenny, Nicholson |

Bleaklow Fragment, John Kenny |

Muybridge Frames, George Nicholson |