Multiple Tonguing for Trombonists

- PDF of Music Examples in this Article

- More Pedagogical Resources at Dr. David Mathie's YouTube Channel

Introduction

As trombone players, we are expected to tongue whatever is put in front of us, assuming we don't need to move our slides much when things get fast. Joking aside, brass players need to accommodate passages that are too rapid to tongue using the normal "Tah" syllable. To do this we use multiple tonguing.

To understand how this tonguing works, clap quarter notes at the speed of ♩ = 108 and say "Tah" in sixteenth notes. Next do the same at ♩ = 112, then ♩ = 116 until it just can't be done. That tempo, usually around ♩ = 120, can be considered your "break point"; beyond that, your tongue simply can't move any faster.

This is where we change to the "Kah" syllable, allowing our tongue to move in a front-to-back motion. Try the same exercise as above saying "Tah-Kah-Tah-Kah" (from now on written T-K-T-K) and you can see how easy it is; our "break point" is now far beyond ♩ = 120.

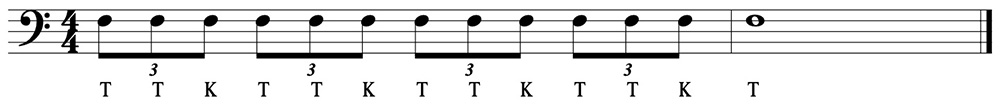

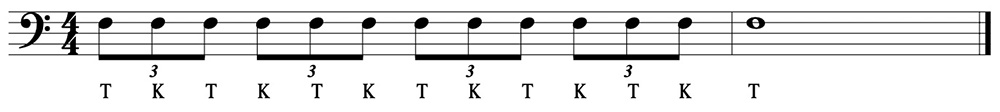

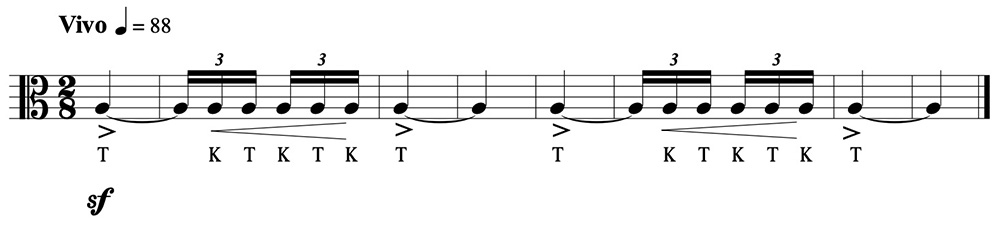

Brass players use two kinds of multiple tongue: double tonguing for duplets, using the syllables TK TK TK TK, and triple tonguing for triplets, using the syllables TTK TTK TTK TTK. Note that there are some disagreements about the triple tongue articulation that I'll address later.

The two examples below show the articulations used for rapid duplets (double tongue) and triplets (triple tongue):

Learning The Multiple Tongue Syllables

I learned how to double tongue during the first rehearsal of a junior high school honor band, where we began with Joseph Wilcox Jenkin's American Overture (what was that conductor thinking?) at full-speed-ahead tempo. If you don't know the piece, the music is marked Allegro molto and the brass have extended and exposed sixteenth-note passages. I decided the piece couldn't be played until the trombonist next to me asked if I knew how to double tongue. I didn't, but by the end of the week I managed to teach myself a weak version.

I don't recommend learning it that way (or jumping into the deep end of the pool to learn how to swim, etc.). Multiple tonguing is best begun well before you need it; I would suggest somewhere in the fourth to fifth year of playing (or, a month before you start the American Overture). Two things are very important when you start this new articulation:

First, make sure you start slowly to develop a strong K syllable, just as strong as your T. Many brass players learn to double tongue at a tempo so fast they learn a weak K syllable and that problem never improves.

Second, create an "overlap" area where you can easily switch back and forth between single tonguing and double tonguing. The area usually begins at sixteenth notes between ♩ = 108 and goes to quarter note = 132, and creating it will prevent you from having a gap in your playing where you cannot single tongue above ♩ = 108 or double tongue below ♩ = 132.

Another advantage to these suggestions is that often tempos change: you may have practiced a passage single-tongued in rehearsals that, in concert, suddenly needs to be double-tongued (conductors get nervous!)

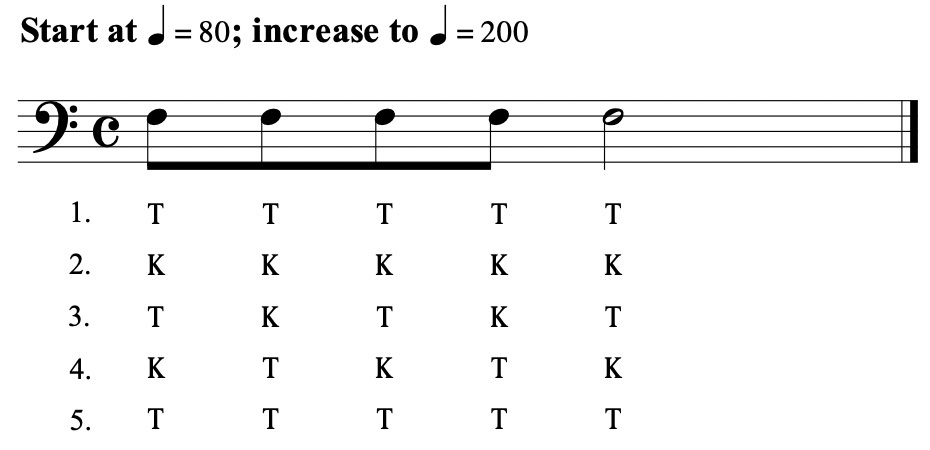

.Here is an exercise designed to learn the double tongue articulation and develop a strong K syllable.

For this exercise, start on a middle F (step 1) and begin the measure slowly and loudly at ♩ = 80, with a hard tongue on each syllable. Next, do the same with the K syllable (step 2). Continue on through step 5 and make sure that each step sounds exactly the same. It will not sound musical, and will necessitate almost "kicking" the K syllable, but the idea is to develop front-to-back TK motion where both syllables match. I would suggest doing this with a metronome for about five minutes a day, repeating it above and below the F3, and keeping the initial tempo for a few days. Then, move the metronome up one notch and repeat at this tempo. Increase the speed until you have reached the upper limit of ♩ = 200.

Notice that the faster you play the more difficult it becomes to form the K syllable, because your tongue is moving too far back and forth. At some point you need to switch to a "Tah-Gah" articulation rather than T-K. The "Gah" consonant uses the middle of the tongue, rather than the back as is need for K, and the movement of the tongue is shortened. This choice of articulation is actually the preferred method among euphonium and tuba players, although I feel that the traditional TK works best for trombonists at most tempos.

It's critical to learn the new multiple tongue articulations slowly to avoid becoming the brass player who can only double-tongue at breakneck speeds.

Learning To Triple Tongue

We learn double tonguing first, usually because in music rapid duplets tend to appear before triplets. Before beginning the triple tongue make sure your K syllable is strong and feels comfortable.

The standard articulation for triple tongue is TTK. This is a bit tricky in that it puts two T syllables in a row, which can be a tongue-twister at first. Begin triple tonguing the same way as double: start very slowly and then increase the tempo, making sure that there is that "overlap" area where you can switch back and forth between a single tongue and triple.

There are some brass players who use the double tongue pattern on triplets, alternating the T and K syllables as seen in the example below.

While there is nothing inherently wrong about this (the end result is how it sounds, not how it's done), there is a disadvantage to this method: it puts the K syllable, rather than the T, on the beat. If your K syllable is as strong as your T, no problem! However that often is not the case. Also, I have found that using this method on a series of repeated triplets loses the triplet feeling that results from using the normal TTK pattern.

Practicing Multiple Tonguing

Once the K syllable is perfected, you need to put this into your daily practice. One good method is to play an etude all the way through, slowly, using only multiple tongue. The two examples below from the Kopprasch etude book show how this is done, one for double tonguing and one for triple.

Another method can be used in during rehearsals: replace passages you normally single tongue with double tongue, regardless of tempo. Go back and forth between tonguing patterns and make sure they match. As I mentioned at the beginning, sometimes you may have to do this in a concert if the tempo is faster than you rehearsed (this has happened to me on a few William Tell Overtures over the years).

Using The Multiple Tongue In Other Rhythmic Patterns

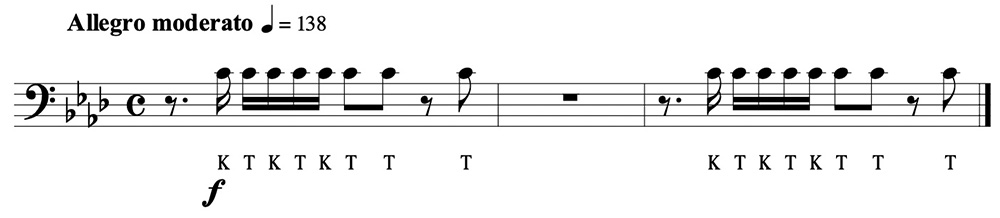

Sometime you will encounter passages that don't fit nicely into traditional double or triple tongue patterns. This often occurs in figures that begin with an upbeat, where you may end up putting a K syllable on a beat that really demands a stronger T syllable. Using the example below, from Sibelius' Finlandia, if you were to begin on a T you would play the two eighth notes on beat three with the K syllable; however, starting the passage on a K puts the eighth notes on a T syllable.

A second example is in the last movement of Scheherazade, where the trombones and tuba alone have a very loud passage with a crescendo to an accented long note on the third and seventh measures. Unless you begin with a K, that note happens on a K syllable and thus becomes very difficult to accent. Using the suggested articulation makes it more musical and more effective.

Summary

Multiple tonguing is used to play passages that are too fast to use the normal single tongue. Switching to the TK or TTK syllables allows us to articulate at almost any tempo. In order to make a seamless transition from single to multiple tongue we must learn the K syllable slowly at first, so it exactly matches the regular T articulation. Also, we need to create an "overlap area" where we can switch back and forth between single and multiple tongue with ease. Once we have learned this technique alternating between the two methods of articulation should be second nature.