An Introduction to Donald S. Reinhardt's Pivot System

There is perhaps no other brass pedagogue whose teachings are so misunderstood and maligned than as that of Dr. Donald S. Reinhardt and his Pivot System for all brass instruments. Although Reinhardt's term "pivot" has been commonly used by many brass players and teachers, the Pivot System has been unfairly dismissed by brass teachers and players for decades. Today, with the addition of new research into brass playing that replicates Reinhardt's, as well as increased availability of information from former student's of Reinhardt's, there is a renewed interest in the Pivot System and the pedagogical genius of Reinhardt.

This article will attempt to summarize the Pivot System in such a way as to touch on the most important concepts of Reinhardt's teachings. A word of caution, however, is necessary for the reader. The Pivot System as a whole is an approach to teaching and practicing brass instruments that is designed to be modifiable and fit each individual player. Such a method is necessarily very detailed, since it needs to cover many different physical and mental differences among brass players. An incomplete understanding of the Pivot System is as likely to work against as many students as it is to help. Therefore the author urges all readers to carefully read this entire article before attempting to implement any of the concepts into his or her playing or teaching. Readers are also highly recommended to read the entire Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, by Donald S. Reinhardt and if possible study directly from a qualified Pivot System instructor. As Reinhardt was fond of saying, "A little knowledge is a dangerous thing."

Furthermore, it is easy to misunderstand the Pivot System to be an approach of detailed analysis of every mechanical procedure of brass performance at all times. While reading this article keep in mind that Reinhardt never had a student work on more than two correctional procedures at a time and only while practicing specific exercises geared towards those corrections. While understanding of the Pivot System includes an awareness of multiple facets of technique, each point is only addressed in practice according to the proper time for each individual student. Once work on brass technique has been completed for the day all Pivot System procedures are to be forgotten and attention is given to the music and expression.

Before going into the details of the Pivot System it may be helpful to understand the background and experiences of Donald Reinhardt.

Donald S. Reinhardt (1908 - 1989)

Donald S. Reinhardt began his musical studies early, beginning with a six hole flageolet at the age of four and progressing from there to many other instruments. His first formal musical instruction began at the age of eight on violin, but his interest at that time was instead on learning to play the French horn. Instructors told him at this time that he would not be able to play the horn or trumpet because his front teeth were uneven and so he began lessons on the trombone.

Donald S. Reinhardt began his musical studies early, beginning with a six hole flageolet at the age of four and progressing from there to many other instruments. His first formal musical instruction began at the age of eight on violin, but his interest at that time was instead on learning to play the French horn. Instructors told him at this time that he would not be able to play the horn or trumpet because his front teeth were uneven and so he began lessons on the trombone.

While his initial progress on the trombone was good, it wasn't long before he reached a barrier in his playing and was sent to another instructor to help him correct his problems. This teacher was also unable to help Reinhardt and he was again sent to another instructor. After eighteen teachers tried and failed to help, Reinhardt resigned himself to playing second or bass trombone since he did not have the required range to play the first chair.

One day an accident flattened the tuning slide of Reinhardt's trombone. After being repaired the instrument was returned to Reinhardt with the counterweight still removed. When Reinhardt played on this front-heavy instrument his horn angle was significantly lower. Because of this lower horn angle the membrane of his lower lip had rolled in and slightly over his lower teeth and for the first time in his life Reinhardt was able to play a high B flat. With a little more experimentation he was able to work his range up to the F above this B flat.

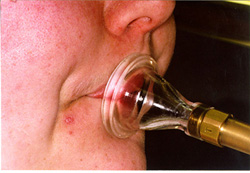

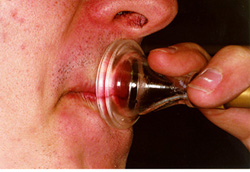

This sparked an interest in how other brass performers played and Reinhardt began to study the embouchures of every brass player he could. Through the use of mouthpiece visualizers and later transparent mouthpieces he discovered that while some players produced their high notes in a manner similar to him, others played exactly opposite. Reinhardt had discovered the difference between upstream and downstream embouchures that became the basis for his approach that he would term the "Pivot System." He would eventually identify four basic embouchure types with five subtypes and eight distinct tonguing types.

In order to test the brass playing principles Reinhardt learned from extensive observation and experimentation he began to give free instruction to all brass instrumentalists for over two years. He would later establish a private studio in Philadelphia, PA where he taught literally thousands of students over a period of greater than 60 years. He became particularly well known for helping students who had exhausted all other approaches and came to Reinhardt as a last resort.

Unlike several other master brass pedagogues, Reinhardt wrote quite extensively on his system, culminating with his publication, The Encyclopedia of the Pivot System. This volume discussed many key points of Reinhardt's teaching approach, including posture, breathing, the role of the tongue, and the embouchure. This text arguably deals with the mechanics of brass playing with more detail and accuracy than any other single volume by any other author.

What is the Pivot System?

The best way to summarize what Pivot System is to use Reinhardt's own words.

The PIVOT SYSTEM (sic) is a scientific, practical, proven method of producing the utmost in range, power, endurance and flexibility on the trumpet, trombone and all other cupped-mouthpiece brass instruments. It was originated not only through forty years of research and experimentation in practical playing, teaching, writing and lecturing to many thousands of professionals, semi-professionals, supervisors, teachers, students, etc., but also through designing and producing personalized mouthpieces and being consultant of instrument design for several leading manufacturers of brass instruments.

This system, working on tried and tested principles, first of all analyzes and diagnoses the physical equipment of the player and then presents a specific, concrete set of rules and procedures which enable the individual to utilize, with the greatest possible efficiency, the lips, teeth, gums, jaws, and general anatomy with which he is naturally endowed. The study of the PIVOT SYSTEM is absolutely essential for all brass instrument performers because strict adherence to a musical approach deprives the student of basic mechanical necessities which are vital to his uninterrupted improvement on the instrument. (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973 page XI)

It is important to reiterate that the goal of the Pivot System is to allow the brass student to work with his or her physical anatomy in the most efficient manner possible. Where other popular brass methods take a more rigid approach to brass playing, the Pivot System utilizes an approach that is catered to each unique individual.

It is this personalized approach that may be responsible for more confusion and misunderstanding about the Pivot System. Advice given to one student may directly contradict with advice given to another. Often times Reinhardt's instructions to a single student would conflict with previous instructions according to this student's level of development. This apparently contradictory advice has caused many to unfairly dismiss the Pivot System.

The Three Primary Playing Factors

Although the Pivot System is named after the embouchure motion Reinhardt referred to as a "pivot" (to be discussed later in this article), the system as a whole takes into account what Reinhardt referred to as the three primary playing factors. These are the entire embouchure formation (including the lips, mouth corners, cheeks, jaw, and entire facial area), the tongue and its manipulation, and the breathing. The goal of the Pivot System is to coordinate all three factors so that they function properly as a synchronized unit. These three playing factors will vary in importance according to the stage of development of the student.

Where many methods place primary importance on breathing, Reinhardt felt that focusing on correcting playing faults by breathing alone was to be likened to a woodwind player playing on a bad reed. "If a very fine oboist selects an excellent instrument but uses a defective reed, the results will suffer regardless of whether his breathing is correct or incorrect. The same holds true in brass playing!" (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, page 6).

Here again is an example of how Reinhardt's instructions often seemed contrary from student to student. Where Reinhardt might suggest to one student to focus on a particular aspect of breathing, to the other he might advise working on embouchure or tonguing. This wasn't because his instruction was untested and in flux, but because he recognized the stage of development for each particular student and precisely understood the focus necessary to achieve the most benefit for each student.

The Sensation Theory

Before discussing the three primary playing factors in more detail it is important to cover Reinhardt's Sensation Theory. This approach to playing a brass instrument has the player relying primarily by feel rather than on sound. The more a player relies on feel the more accuracy he or she will achieve. According to Reinhardt, most consistent brass players predominate in their ability to play by feel over sound, even though they are usually not aware of this fact (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, page 13).

In order to fully understand the Sensation Theory it is essential to comprehend that there can be two different sensations to playing, the pre-playing sensation and the playing sensation. The pre-playing sensation is the feeling a brass player has in the embouchure formation and general anatomy a split second prior to attacking a note. The playing sensation is the feeling the player has during the actual producing of a pitch.

The Sensation Theory of playing strives to merge both the pre-playing and playing sensations into one unified sensation. The purpose of the warm up should be to connect these two sensations into one sensation and develop consistency from one day to the next. "A consistent unified sensation means consistent performance; widely separated pre-playing and playing sensations mean inconsistent performance!" (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, page 14). In order to maximize the student's attention on the feel most exercises for playing mechanics are to be done with the eyes closed.

It must be clarified that the purpose of the Sensation Theory is not to avoid hearing altogether, but rather to reduce the brass student's reliance on sound. A consistent sense of the feel of playing will allow the brass player to play with consistency, regardless of the acoustical situation.

Posture and Breathing

Of the three primary playing factors, posture and breathing have gotten the most attention from other brass pedagogues. Since this topic has been similarly covered by others less attention will be given in this article concerning posture and breathing than to tonguing and embouchure. This is not because these areas are considered less important in the Pivot System. This article will instead deal more with information discovered and developed by Reinhardt that is unique to the Pivot System.

Reinhardt's approach to posture was similar to what other brass teachers have written, but with perhaps more detail on specifics. Like others, Reinhardt felt that correct posture was the foundation of correct breathing. In order to accomplish correct posture the student was instructed to keep the head in a position described as slightly backwards and downwards with a relaxed neck. The spine should be slightly arched backwards as well with the arms kept away from the body. This body position is to be maintained regardless of whether the student is sitting, standing, or marching. Reinhardt further warned, "Remember, the word "relax" does not mean collapse! Relaxing suggests a loosening of the muscles, but collapsing indicates an alteration of some kind or other." (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, page 19).

Breathing in the Pivot System has many similarities to other brass teacher's approaches. Reinhardt advocated taking a slow inhalation whenever possible, avoiding any lifting of the shoulders during the inhalation, and never delaying the exhalation to attack a note at the peak of the inhalation. The exhalation should start from as low as possible, in the pelvic region, in order to maximize the ability to use the greatest amount of air in the most efficient manner. These are not unique to the Pivot System and many other texts and method books concerning brass playing recommend the same.

Fewer other brass pedagogues have paid as much attention to the features of the diaphragm and abdominal regions when the breathing is functioning correctly. Reinhardt observed that during the initial attack, regardless of what range the pitch to be played, the diaphragm and abdominal regions should lift, not protrude, in coordination with the tonguing. This lift should only occur on the initial attack, never on subsequent articulations, even if the player is attacking successive detached notes (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, page 34). The diaphragm and abdominal lift is also more pronounced the higher the pitch to be played (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, page 53).

Contrary to some brass instructors, Reinhardt recommended that the brass player strive to inhale the exact amount of air to be used to play each particular phrase so that at the completion of each phrase the player has exactly the same amount of air in his or her lungs as just prior to beginning the inhalation for that phrase. Reinhardt called this particular procedure "timed-breathing." Likening this to reading literary passages out loud, Reinhardt suggested his students master this approach in order to avoid over breathing, a cause of dizziness and strain, and under breathing, which can manifest in a thin sound and lack of coordination of the basic playing factors. This advanced technique also allows for the maximum efficiency while breathing since a passage played softly will require less air than the same passage played loudly. When this technique is mastered the brass player will never need to exhale stale air prior to inhalation and will never find himself or herself running out of air.

One area where the Pivot System differs from virtually all other approaches is through the mouth corner inhalations. Where other methods either ignore this issue altogether or advocate opening the mouth and breathing through the mouth center, Reinhardt instructed his students in a detailed procedure for setting the mouthpiece and how to inhale in such a way that air can be efficiently taken into the lungs while disturbing the embouchure formation as little as possible. This is accomplished by first placing the mouthpiece on the lips with the lips and jaw already firmly set in position to begin buzzing. Keeping the lips just touching in the mouth center, the mouth corners are pulled slightly back and the tongue receded out of the way to breath through the mouth corners. Since the goal is to disturb the embouchure formation as little as possible during the inhalation care is taken to keep the head and jaw still and keep the instrument angle the same during the inhalation as when playing.

Tonguing and Attacks

Reinhardt's observations about how the tongue functions in brass playing are covered in detail in The Encyclopedia of the Pivot System of the Pivot System.

The tongue as used in the PIVOT SYSTEM has three principal duties: one, the level of the tongue-arch is one of the factors for the control of range; two, the length of the tongue backstroke is one of the determining factors for volume and speed; and three, the tongue-level directs and governs the size of the cone-like air column so that it may strike the back of the compressed embouchure formation to produce the lip-vibrations for the particular tone to be played. (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, page 82.)

Although many older texts on brass playing often discourage the use of arching the tongue at different levels according to the register to be played, Reinhardt discovered that the level of the tongue arch is the governing factor of the size and direction of the air column as it passes over the tongue on its route to the compressed embouchure formation. If this air column is not directed properly the air will encounter more embouchure resistance. For the lower register the tongue arch should be in a similar position as if the player saying "ah." In the middle register the tongue arch should be closer to "oo" and the tongue arch should be similar to "ee" for the upper register.

In the Pivot System attention is also given to the backstroke of the tongue. It is the backstroke of the tongue that releases the air column so that it may strike the compressed embouchure formation and set the vibration of the lips. Working in conjunction with the breathing, a shorter and slower tongue backstroke will assist in a softer dynamic level. Conversely, for a loud dynamic level the tongue backstroke should be long and quick (Reinhardt, Pivot System for Trumpet page 7).

In addition to these and other observations basic to all brass players Reinhardt identified and labeled eight distinct tongue types, of which any may be correct according to the individual brass player's anatomy and musical circumstances.

Tongue-Type One

Brass players who specialize in playing in the upper register often use Tongue-Type One. With this tongue type the tongue spreads and the tongue sides are held in contact against the inside of the upper teeth immediately following the tongue backstroke. The tongue in this position forces the air column to thin down and aids this brass player in producing very fast lip vibrations. Reinhardt did not generally recommend this tongue type, as it typically causes limitations while playing in the lower register (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 87).

Tongue-Type Two

The most common tongue type is Reinhardt's Tongue-Type Two. This tonguing type, which is also recommended by many other brass texts and method books, is distinguished by the tongue striking the back of the upper teeth or upper gums and then arching and hovering inside the mouth according to the register being played. It permits freedom of articulation in all registers, but will sometimes also permit the jaw to recede too much, causing other playing difficulties (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 88).

Tongue-Type Three

Reinhardt's Tongue-Type Three performers are in the minority. Although Reinhardt admonished his student's to never permit the tongue to penetrate between the teeth, certain brass players have a lower lip that is long and thick enough coupled with very short lower teeth. For these players immediately after the tongue strikes the back of the upper teeth or upper gums it will snap back and then return to the lower lip. The tip of the tongue will then rest on the lower lip while sustaining and slurring with performers of this tongue type (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, pp. 88-89). Some brass methods refer to this tonguing type as a "tongue controlled embouchure."

Tongue-Type Four

Also in the minority is the Tongue-Type Four. This type is identical to Tongue-Type three with the exception that the tongue strikes the lower lip for the attack, instead of the back of the upper teeth or upper gums (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 89).

Tongue-Type Five

Tongue-Type Five is another one of the more common tonguing types. After the tongue strikes the back of the upper teeth or upper gums the tip of the tongue lunges down and makes contact with the gully where the lower gum meets the floor of the mouth. This tongue type also provides support for the jaw as the tongue presses forward to create a higher tongue arch level while ascending. Individuals who adopt this tongue type must have a sufficiently long enough tongue to accommodate this forward tongue pressure without loosing contact with the gully (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, pp. 89-90).

Tongue-Type Six

Tongue-Type Six is virtually identical to Tongue-Type Five, excepting that these individual's do not possess tongues as long as those who belong to Tongue-Type Five. This tongue type will attack with the tip of the tongue striking the back of the upper teeth or gums, following which it will drop down to the gully where the lower gums and floor of the mouth meet. Unlike Tongue-Type Five, the higher tongue arch level for ascending is created by pulling the tip of the tongue back in the mouth, while keeping the tip touching the floor of the mouth. To descend the Tongue-Type Six player pushes the tongue tip forward towards the gully and flatten the tongue. This tongue type does not provide the same jaw support as Tongue-Type Five (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 90).

Tongue-Type Seven

Another rare form of tonguing is Reinhardt's Tongue-Type Seven. Players belonging to this tongue type slur and sustain pitches identically to Tongue-Type Five. The difference in this tonguing type is that pitches are attacked through the tip of the tongue striking the back of the lower teeth or lower gums. This tongue type is sometimes used by players who play with the jaw in a very protruded position (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, pp. 90-91).

Tongue-Type Eight

The last tongue type to be discussed, Tongue-Type Eight, is also one of the infrequent tongue types. This type combines elements from Tongue-Types Six and Seven. In Tongue-Type Eight the tongue strikes the back of the lower teeth or lower gums for the attack and moves to the gully or floor of the mouth. When ascending the tongue arch level is raised by pulling the tongue back without allowing the tip of the tongue to lose contact with the floor of the mouth. When descending the Tongue-Type Eight player lowers the tongue arch level by pushing the tongue forward towards the gully and keeping the tip in contact with the floor of the mouth (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 91).

The tongue type that should be adopted by the brass player is determined by the general physical anatomy of the individual and specific musical and mechanical demands, not how a teacher, well known writer, or famous player tongues. It is possible to perform successfully on any of these tongue types, provided that the tongue type is correct for the individual's physical characteristics. If, for example, a player has a long enough tongue, adopting Tongue Type Five can help with additional jaw support. Some players find Tongue Types Three and Four, the "tongue controlled embouchures," very helpful in the development of the upper register. When a player attempts to adopt a tongue type that is inappropriate for his or her anatomy, however, the results will be unsatisfactory.

Although it is not as commonly instructed today as in older method books, allowing the tongue to penetrate between the lips and teeth for the attack is still a common playing fault, particularly in the lower register. According to Reinhardt, this playing characteristic causes many difficulties. This flaw typically causes the player to release mouthpiece pressure to allow the tip of the tongue to penetrate the lips resulting in the mouthpiece shifting around on the lips. This constant mouthpiece bobbing can then cause a myriad of playing difficulties. Reinhardt wrote:

"Whenever a performer permits his tongue to penetrate between his teeth and lips, he is actually opening them to allow the tip of his tongue to penetrate between them. In so doing, he is subconsciously depending upon the timing of his reflexes to bring his lips together again for the purpose of vibrating. Some players get by in this manner for years but as they advance in age and their reflexes slow down, the real playing difficulties commence." (- Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, pp. 100-101.)

Embouchure

Although Reinhardt's research and instruction with breathing and tonguing was detailed and precise, his insights into the brass player's embouchure is where his research was most original. His descriptions of the four basic embouchure types and five subtypes more accurately describes the way a brass player's embouchure functions while functioning correctly than any other author's. His corrective procedures for embouchure difficulties based on the student's embouchure types, coupled with differences inherent to each individual student, have been shown to be highly effective.

In order to understand the nine embouchure types described by Reinhardt it is important first to understand the two basic blowing categories, upstream and downstream.

In 1962 Phillip Farkas published a very popular book entitled "The Art of Brass Playing." In this text Farkas describes his theories about the brass player's embouchure, including his hypothesis that it goes against logic to "violently deflect" the air stream downward at the point of where the air moves past the lips (Farkas, The Art of Brass Playing, page 7). According to Farkas, lining up the upper and lower teeth with one another through proper jaw positioning will result in the air stream traveling straight into the shank of the mouthpiece and provide better results (Farkas, The Art of Brass Playing pages 8-9).

Eight years later, in 1970, Farkas published a book entitled "A Photographic Study of 40 Virtuoso Horn Player Embouchures." This newer text shows 40 French horn players' embouchure while playing into mouthpiece visualizers. It is interesting to note that out of these subjects 39 were noted to be blowing the air downward and one was directing the air upward. None were seen to be blowing their air stream straight towards where the shank of the mouthpiece would be.

This later publication by Farkas replicates research published by Reinhardt as early as 1942. In his text Pivot System for Trombone, A Complete Manual With Studies Reinhardt briefly described his four basic embouchure types with descriptions of how the air stream can leave the vibrating points of the lips in either an upward or a downward direction. Doug Elliott, a student of Reinhardt's from 1974-1984, wrote concerning air stream direction, "When the placement is more on the top lip, the top lip will predominate into the mouthpiece, and the air will blow down. When the placement is more on the bottom lip, that lip predominates, and the air blows up. If the placement is close to half-and-half, one lip or the other will inevitably predominate, so the air stream will go either up or down." (Elliott, 1998).

Other research into brass embouchures confirms that the air stream travels past the lips almost always in an upward or downward direction, rarely straight into the shank. The author of this article analyzed the embouchures of 34 trombonists and none was observed to be blowing straight into the shank of the transparent mouthpiece utilized for this study (Wilken, 2000). A study of trombone embouchures using high-speed photography by Lloyd Leno (1987) confirmed the presence of both upstream and downstream types of embouchures. Leno noted that the lip alignment within the mouthpiece is the determining factor of air stream direction, not the mouthpiece angle, jaw alignment, or player's teeth. He determined that downstream embouchures have a higher mouthpiece placement, the upper lip overlapping the lower lip, an increased amount of lower lip used for the lower register, and a more active vibration of the upper lip. Upstream embouchure types had the reverse, except for a difficulty observing an overlap of the lower lip over the upper lip. Leno also noted that both embouchure types directed the air stream closer towards the shank of the mouthpiece for lower pitches, and closer towards the rim (upper rim for the upstream, lower rim for downstream) for higher notes (Leno, 1987, p. 46-47).

The Pivot

Before discussing Reinhardt's embouchure classifications the subject of the pivot, an often misunderstood phenomenon, should be discussed. Perhaps the clearest description of how Reinhardt defined a pivot is in his own words.

The PIVOT is controlled by pulling down or pushing up the lips on the teeth with the rim of the mouthpiece. The outer embouchure...and the mouthpiece move vertically (some with slight deviations to one side or the other) as one combined unit on the invisible vertical track of the inner embouchure ...; however, the position of the mouthpiece on the outer embouchure must not be altered in any way (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 194).

It is common for individuals who misunderstand the Pivot System to confuse this motion of the mouthpiece and lips sliding along the teeth as a single unit instead as a tilting of the horn angle. This misunderstanding may have been in a large part due to the following statement by Reinhardt in his Pivot System Manuals for Trumpet and Trombone.

Pivoting is the transfer of what little pressure there is used in playing from one lip to another. . . The instrument is slightly tilted to get the tone at its most open point (Reinhardt, Pivot System Manual for Trombone, 1942, p. 23).

Dave Sheetz wrote about this precise quote in his article "Gone But Still Important." In this article Sheetz addressed a discussion with Doug Elliott where Reinhardt reported his wishes that he had never published this particular statement. Reinhardt clarified in his later publication, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System.

In the early stages of PIVOT development, some angular motion of the instrument is often prescribed, so that the performer may thoroughly familiarize himself with the proper jaw manipulation and its attendant sensations for his particular physical type. . . With consistent and correct daily study and practice, all exaggerated movements soon subside until they are negligible (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 19).

John Froelich (1990) studied the level of mouthpiece pressure and the direction the pressure as applied among trombonists of varying levels and stylistic demands. Using a tool designed to measure direct (vertical) and shear (horizontal) mouthpiece forces, Froelich determined that there were differences in the mouthpiece forces between professional symphony trombonists, other professional trombonists, and student trombonists. Froelich found that the symphony trombonists used the least direct and shear forces and the student trombonists used the most direct and shear forces. Froelich recommended that the symphonic model be adapted for all trombonists (p. 23). At a surface level Froelich's advice that the symphonic model should be adopted seems sound, since these players were the most experienced players utilized as test subjects for this study. When Reinhardt's advice that all exaggerated movements are reduced as the player progresses is taken into account, Froelich's study confirms that as a brass player reaches the later stages of development that the amount of pivot does indeed become reduced, often to the point of imperceptibility.

The eventual goal of the pivot is to develop the appropriate lip pucker. When this stage is reached by a Pivot System student the pivot is typically quite unnoticeable to the eye.

Generally speaking the pivot is only employed for intervals of a perfect fourth or larger. Over-pivoting and under-pivoting, particularly over-pivoting in the low register, can be quite detrimental to the performer, and the brass player needs to be ever conscious of letting the core of the sound determine the amount to pivot.

The pivot is a natural and necessary phenomenon for successful brass playing. All successful brass players appear to utilize a pivot, however most are not even aware of it. In this author's study all 34 trombonists were shown to utilize a pivot, even though most had never received any instruction in how to pivot or were even aware of it (Wilken, 2000). The pivot is essential because it allows the player to line up the lips over the entire playing range in such a manner that the teeth do not impede the lip vibrations.

Essentially, as a brass player ascends the direction of the pivot will either be in an upward or downward direction, with some deviations to one side or another, depending on the individual's embouchure type. Performers who ascend by pushing the lips and mouthpiece as one unit up towards the nose fall under Reinhardt's Pivot Classification One. Reinhardt defined Pivot Classification Two as those performers who ascend by pulling the lips and mouthpiece as one unit down towards the chin. In both Pivot Classifications the direction of the pivot to descend will be in the opposite direction.

Click here to view a video of Pivot Type Two in MPEG format.

In order to determine the correct pivot type for each study Reinhardt developed what he called the "Pivot Test." Reinhardt would closely observe the student play an ascending slur from a middle range pitch, usually concert B flat, to the F a perfect fifth above or B flat one octave above. Often the direction of the pivot is obvious just watching, but it can be useful to test both pivot types. One type will work better for the ascending slur, the sound will be more focused and the slur will be easier to play. This is the correct pivot for the individual to employ. At times the correct pivot will still be difficult to hear. It is also useful to listen carefully to intonation, since the incorrect pivot will often sound the higher pitch as flat.

Reinhardt's Embouchure Types

Through extensive observation Reinhardt observed that some brass players exhibited similarities in physical features as well as embouchure characteristics. He was able to break down these similar physical and playing characteristics into four basic embouchure descriptions, with five subtypes of these basic types. Although each individual player will have unique embouchure characteristics virtually every player can be categorized into one of these nine types. Sometimes players can be noted to be switching between two or more embouchure types, a problem to be avoided in the Pivot System.

Before discussing the nine embouchure types in more detail it is important to note that Reinhardt classified each student's type as "for now." In other words, students of Reinhardt were never forced to stick with one particular type, but instead were instructed to allow their embouchures to develop naturally in such a manner that it worked with their physical features, rather than against them. Furthermore, with only one exception, Reinhardt never changed a student's embouchure since 1960, but allowed type changes to occur naturally. The one exception was a student who insisted upon the embouchure change (Everett, 2000, p. 6).

Embouchure Type I and Type IA

The Type I and Type IA embouchures are rarer than most of the other types. These player's upper and lower teeth meet when the jaw is in its natural position. Oddly enough, this teeth and jaw structure appears to inhibit anything other than a very high mouthpiece placement (downstream Type I) or very low (upstream Type IA) mouthpiece placement from working efficiently. Other than the position of the teeth, these types are virtually identical to other embouchure types while the musician is playing. Type I embouchures are identical while playing to either the Type IIIA or Type IIIB embouchures and the Type IA embouchure is identical to the Type IV embouchure while playing. Because of this fact, the Type I and Type IA embouchures will not be covered in detail here (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 205).

The Type I and Type IA embouchures are rarer than most of the other types. These player's upper and lower teeth meet when the jaw is in its natural position. Oddly enough, this teeth and jaw structure appears to inhibit anything other than a very high mouthpiece placement (downstream Type I) or very low (upstream Type IA) mouthpiece placement from working efficiently. Other than the position of the teeth, these types are virtually identical to other embouchure types while the musician is playing. Type I embouchures are identical while playing to either the Type IIIA or Type IIIB embouchures and the Type IA embouchure is identical to the Type IV embouchure while playing. Because of this fact, the Type I and Type IA embouchures will not be covered in detail here (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 205).

Embouchure Type II and Type IIA

The Type II and Type IIA embouchures are similar to the Type I embouchures in that they are distinguished by the natural position of the upper and lower teeth. Players belonging to this rarer type have lower teeth that protrude in front of the upper teeth when the jaw is in its resting position. Because of this teeth and jaw position these individuals will almost always play with an upstream embouchure, necessitating a mouthpiece placement with more lower lip. Other than the position of the player's teeth while the jaw is in its resting position, the Type II embouchure is virtually identical to the Type IV embouchure. The Type IIA embouchure are very similar to the Type IVA embouchure while playing. Because of these similarities the Type II and Type IA embouchures will not be covered here in detail (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, pp. 206-207).

Embouchure Type III

The Types III, IIIA, and IIIB are much more common than the Types I, IA, II, and IIA. These player's lower teeth naturally recede behind the upper teeth when the jaw is in its resting position. Players belonging to these types rarely protrude their lower jaw past the point where the upper and lower teeth are even and all three types place the mouthpiece with more upper lip inside the mouthpiece cup.

Reinhardt's Type III embouchure, often called the "Jelly Roll Type," plays with a mouthpiece placement with usually only slightly more upper lip inside the mouthpiece cup. Because there is more upper lip than lower lip inside the mouthpiece the air stream is directed at a downward angle inside the mouthpiece cup. The jaw is typically receded beneath the upper and because of this the horn angle is typically tilted lower, often quite extremely. In addition to the receded lower jaw, one of the main distinguishing features of this embouchure type is that the player's lower lip membrane is positioned in and slightly over the lower teeth. As this type player ascends the lower lip roll becomes more pronounced.

Reinhardt's Type III embouchure, often called the "Jelly Roll Type," plays with a mouthpiece placement with usually only slightly more upper lip inside the mouthpiece cup. Because there is more upper lip than lower lip inside the mouthpiece the air stream is directed at a downward angle inside the mouthpiece cup. The jaw is typically receded beneath the upper and because of this the horn angle is typically tilted lower, often quite extremely. In addition to the receded lower jaw, one of the main distinguishing features of this embouchure type is that the player's lower lip membrane is positioned in and slightly over the lower teeth. As this type player ascends the lower lip roll becomes more pronounced.

The Type III embouchure usually utilizes Reinhardt's Pivot Classification Two, pulling down towards the chin to ascend and pushing up towards the nose to descend. Since Pivot Classification One is not uncommon, a Pivot Test is essential in order to avoid incorrect advice (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 208).

In many cases a Type III player will have difficulties with the extreme upper register, changing types as he or she plays from around a concert F above high B flat or higher. This is particularly common with trumpet players, due to the smaller mouthpiece size and increased demand on faster lip vibrations. In these situations Reinhardt would reclassify this player as a Type IIIA or IIIB, according to their embouchure in the extreme upper register. True Type III players have a jaw that cannot protrude far enough to make a playing on a Type IIIA or Type IIIB possible. (Sheetz, PivoTalk Newsletter, Vol. 2, #3, p. 3).

One common difficulty Type III players have is their necessity of playing with the bell directed towards the floor because of a receded lower jaw. Players with this trouble need to be careful to not put their head too far back and place undue strain on their neck, restricting the throat (Sheetz, Quirks of the Types). Dave Steinmeyer, Conrad Gozzo, Tommy Dorsey, and Reinhardt himself are good examples of Type III brass players.

Embouchure Type IIIA

The Type IIIA embouchure tends to play with the mouthpiece placed quite high, often just under the nose with trombonists. These players also typically protrude the jaw more than the standard Type III players, but never to the point of thrusting the lower teeth beyond the upper teeth. With the jaw in a more protruded position the horn angle tends to be almost horizontal, and sometimes even higher. Because the upper lip predominates inside the mouthpiece cup this type also is classified as a downstream type.

The Type IIIA embouchure tends to play with the mouthpiece placed quite high, often just under the nose with trombonists. These players also typically protrude the jaw more than the standard Type III players, but never to the point of thrusting the lower teeth beyond the upper teeth. With the jaw in a more protruded position the horn angle tends to be almost horizontal, and sometimes even higher. Because the upper lip predominates inside the mouthpiece cup this type also is classified as a downstream type.

Type IIIA performers always utilize Pivot Classification One, pushing up towards the nose to ascend and pulling down towards the chin to descend. When a student found that Pivot Classification Two worked more efficiently Reinhardt would classify the player as a Type IIIB (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, pp. 208-209).

Brass players belonging to Reinhardt's Type IIIA embouchure often have a tendency to raise their horn angle while inhaling. When they bring the mouthpiece back down to play they crash the mouthpiece rim against the lips, causing swelling and inhibiting endurance. Type IIIA players of larger mouthpieces, such as trombonists, may find that their nose gets in the way of their ascending pivot, necessitating practice increasing their lip pucker instead of relying exclusively on their pivot to ascend (Sheetz, Quirks of the Types). Joseph Alessi, Lyn Biviano, Arturo Sandoval, and Bill Watrous are some examples of Type IIIA embouchures.

Embouchure Type IIIB

The Type IIIB embouchure is perhaps the most common one, especially among symphonic brass players, and is therefore most frequently described in method books by brass pedagogues who recommend a single embouchure for all students. These players typically don't place the mouthpiece as high as a Type IIIA embouchure or as low as a Type III. The upper lip still predominates inside the mouthpiece cup and this embouchure is therefore classified as a downstream embouchure. The lower teeth of a Type IIIB player is receded beneath the upper teeth on these players and the horn angle is usually slightly lower than a IIIA.

The Type IIIB embouchure is perhaps the most common one, especially among symphonic brass players, and is therefore most frequently described in method books by brass pedagogues who recommend a single embouchure for all students. These players typically don't place the mouthpiece as high as a Type IIIA embouchure or as low as a Type III. The upper lip still predominates inside the mouthpiece cup and this embouchure is therefore classified as a downstream embouchure. The lower teeth of a Type IIIB player is receded beneath the upper teeth on these players and the horn angle is usually slightly lower than a IIIA.

Type IIIB players always utilize Pivot Classification Two, pulling down towards the chin to ascend and pushing up to descend. When a Type IIIB student finds that Pivot Classification One is more efficient this player should be reclassified as a Type IIIA (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 209).

Type IIIB embouchure players tend to have great flexibility and an easier time playing with a darker tone quality, but also have a tendency to become so concerned with a fat sounding lower and middle register that they play with too open an aperture. This results in difficulties playing above a concert D flat above high B flat. Because this type utilizes Pivot Classification Two it is also common for these players to dig the mouthpiece rim into their upper lip, causing swelling and trouble with endurance (Sheetz, Quirks of the Types). Examples of Type IIIB brass players include Chuck Findley, Rafael Mendez, and Lyn Nicholson.

Embouchure Type IV

Embouchure Types IV and IVA players have lower teeth which recede beneath the upper teeth while their jaw is in their resting position, but since these types place the mouthpiece with more lower lip inside the cup than upper lip the air stream is directed at an upward angle, regardless of the position of the jaw while playing or horn angle.

In addition to placing the mouthpiece lower on the lips, Reinhardt's Type IV embouchure plays with the lower jaw quite protruded beyond the upper, in spite of the jaw's natural position. While playing this embouchure type is identical to Reinhardt's Type II embouchure. Due to the protruded position of the lower jaw the horn angle of this embouchure type is very high, sometimes higher than horizontal.

In addition to placing the mouthpiece lower on the lips, Reinhardt's Type IV embouchure plays with the lower jaw quite protruded beyond the upper, in spite of the jaw's natural position. While playing this embouchure type is identical to Reinhardt's Type II embouchure. Due to the protruded position of the lower jaw the horn angle of this embouchure type is very high, sometimes higher than horizontal.

Type IV players almost always utilize Pivot Classification Two, pulling down to ascend and pushing up to descend. There are exceptions, however, so a Pivot Test should always be used to ensure proper instruction. In those exceptions Reinhardt found that the mouthpiece placement was often too low for this player's embouchure (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, p. 210).

It is common for Type IV players to change their horn angle while inhaling and crash the mouthpiece against the lips for initial attacks, similar to the Type IIIB embouchure (Sheetz, Quirks of the Types). Good examples of Type IV brass players include Wynton Marsalis, Jon Faddis, Doc Severinsen, and Dick Nash.

Embouchure Type IVA

Type IVA embouchures are identical to Type IV embouchures with a couple of exceptions. Like the Type IV, these players place the mouthpiece with more lower lip inside the mouthpiece and the air stream is directed in an upward direction. Unlike the Type IV embouchure, Type IVA players keep their jaw in a somewhat receded position so that the lower jaw is beneath the upper while playing, resulting in a downward horn angle.

Type IVA embouchures are identical to Type IV embouchures with a couple of exceptions. Like the Type IV, these players place the mouthpiece with more lower lip inside the mouthpiece and the air stream is directed in an upward direction. Unlike the Type IV embouchure, Type IVA players keep their jaw in a somewhat receded position so that the lower jaw is beneath the upper while playing, resulting in a downward horn angle.

The Type IVA embouchure typically utilizes Pivot Classification Two, pulling down to ascend and pushing up to descend, but there are some deviations to this principle (Reinhardt, Encyclopedia of the Pivot System, 1973, pp. 210-211).

The type IVA embouchure is a very delicate embouchure type, which may be one reason why so many brass method books discourage utilizing this embouchure. When the Type IVA placement is a little wrong the whole embouchure system can often break down completely. Similar to the Type IIIB embouchure, Type IVA players often dig into their upper lip while pivoting down to ascend, causing excessive swelling (Sheetz, Quirks of the Types). Kai Winding, who studied directly from Reinhardt, was a good example of a Type IVA embouchure, as well as Buddy Childers.

Suggestions for Students and Teachers

With an approach that is so personalized as the Pivot System it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to effectively learn the Pivot System without personal contact with someone experienced in Reinhardt's teachings. The best way to learn the Pivot System today is through instruction from a qualified Pivot System teacher. With increased availability of information concerning the Pivot System more instructors who have not studied directly from Reinhardt are now able to effectively teach the Pivot System than ever before.

Anyone interested in learning about the Pivot System must obtain an unabridged copy of Reinhardt's Encyclopedia of the Pivot System of the Pivot System, the most comprehensive text on the subject. Other essential books include Reinhardt's Pivot System for Trumpet and Trombone; A Complete Manual With Studies.

It is also important to reiterate that in spite of the detailed analysis that the Pivot System uses to develop strong brass technique, work on brass mechanics is never to exceed more than two corrective procedures at a time. A qualified instructor of the Pivot System will be able to isolate the exact procedures a student should work on at the correct time for the student's development. Once practice on these corrective materials has concluded for the day the student will be instructed to forget the details of the Pivot System and instead focus on expression and music. Success in the Pivot System depends on the student's and teacher's abilities to simplify all the technical details and allow the mechanics of brass playing to become unconscious playing procedures.

Barring personalized instruction in the Pivot System and access to Reinhardt's writings, here are several practice suggestions to start with.

Play on a wet embouchure.

Although many fine players do play on a dry embouchure, and in many cases Reinhardt would actually prescribe students to play dry, a wet embouchure should be adopted whenever the player's development and musical demands permit. In the Pivot System the embouchure is to be saturated with saliva in a three-part process. First, the player should wet the teeth and gums to facilitate changing registers without the lips sticking to the teeth. Next, the mouth corners should be saturated in order to keep the lips from sticking together during the standard mouth corner inhalations. Lastly, the entire embouchure formation should be wet.

Playing with a wet embouchure offers many advantages over dry, including increased embouchure response and fewer problems with cuts or sores on their lips. Brass players who cannot adopt a truly wet embouchure can often adopt a partially wet embouchure, leaving the top or bottom lip dry, or even both lips. Keeping the teeth, gums, and mouth corners wet, however, is usually necessary to provide lubrication for both the pivot and the mouth corner inhalations.

Always place the mouthpiece on lips set with "buzzing firmness."

It is very common for brass players, even very fine ones, to set the mouthpiece upon their lips devoid of form and then firm the lips to play. For these players, placing the mouthpiece on lips already firmed to buzz feels unusual and often causes difficulties at first. Once the sensation of placing the mouthpiece in this manner is grown accustomed to students of the Pivot System usually find their placement becomes more consistent and their accuracy improves.

After wetting the lips appropriately, the membrane of the lower lip should be drawn slightly in and over the lower teeth. The upper lip should then reach down as if saying, "Em" so that it makes contact with the lower lip, slightly overlapping it. The mouthpiece should then be placed with the lips set in this manner and the jaw in its normal playing position.

Always place, inhale through the mouth corners, and then blow.

One of the most common playing difficulties encountered by brass players can be traced back to allowing the embouchure formation to distort when breathing. Consistency in playing, particularly as the brass player ages and reflexes naturally slow down, is dependent upon a consistent placement and breathing procedure. By placing the mouthpiece on the lips first and then inhaling through the mouth corners with the mouth center just touching the brass player will maintain a consistent embouchure throughout his or her entire range.

When breathing through the mouth corners it is very important to avoid pulling the mouth corners up into a smile position, which can result in distortions of the embouchure formation. With the center of the lips just touching bring the mouth corners back slightly and inhale with the tongue in a position as if saying "Imm." Receding the tongue in this manner brings it out of the path of the inhaling air and allows for a more relaxed and complete breath. At the initial attack following the inhalation the mouth corners should snap forward to the buzzing position.

For more information on these procedures see Dave Sheetz's master class article, "Setting Your Embouchure."

The Three Daily Playing Calisthenics

In order to develop the muscle strength necessary for a firm embouchure formation Reinhardt prescribed three daily exercises to practice away from the horn: The Pivot System Buzzing Routine, The Jaw Retention Drill, and the Pencil Trick Routine. Of the three, the most difficult one to describe is the Buzzing Routine.

The Buzzing Routine

Since buzzing incorrectly can actually impede progress it is essential to follow Reinhardt's instructions carefully while working on this exercise. First, all buzzing procedures should be done on an embouchure completely saturated with saliva, regardless of whether the brass player plays on a wet embouchure, dry embouchure, or combination of the two during normal playing. The membrane of the lower lip is to be rolled slightly in and over the lower teeth while the upper lip reaches down as if saying "Em." Without a mouthpiece rim this helps to set up the lips into position for a downstream buzz, regardless of the players normal playing embouchure. Buzzing with an upstream embouchure can actually cause damage to the embouchure muscles at worst and at least sets up this kind of practice in such a way as to work against the normal playing embouchure, so upstream players should always buzz in this downstream manner. Buzzing should be done lightly enough so that the air stream is directed from only one spot on the embouchure formation, even if it isn't the same spot when actually playing. All buzzing procedures are most efficient when the buzz is commenced with a no tongue attack, as if saying "hoo." Never practice the buzzing routine when you are fatigued and this routine is not intended for use as a warm up procedure.

With those points in mind, set the lips for buzzing firmness and buzz a middle concert B flat to the fullest extent of your breath. When the buzz is completed practice the mouth corner inhalation by placing your finger against the center of your embouchure formation to help keep the mouth center just touching. Once the mouth corner inhalation has become comfortable enough the finger contact can be eliminated. Buzz and inhale this way three times, attempting to make each successive buzz higher than the next. Rest following this exercise. Once this routine has been practiced daily for several weeks this can be extended to buzzing simple melodies or patterns.

The Buzzing Routine is very helpful to strengthen embouchure muscles, particularly the small knots of muscles at the mouth corners and just below the mouth corners. It is also particularly useful to help students who have a tendency to bring their mouth corners back into a smile for their upper register, thereby limiting their range, endurance, and tone.

A cautionary note, while buzzing into the mouthpiece, with or without the instrument, can be a very useful practice procedure for some performers, particularly the Type III and IIIA embouchures, this type of practice can be damaging for many players, especially the upstream Types IV and IVA. If you're not certain of your embouchure type, it is best to avoid buzzing into the mouthpiece in this manner.

The Jaw Retention Drill

The Jaw Retention Drill was prescribed by Reinhardt to immediately follow the Buzzing Routine. In this exercise students are instructed to roll the lower lip membrane slightly in and over the lower teeth first and then protrude the jaw as far as possible, stopping before strain is felt. Hold this position for around ten seconds at first, but always stop if you experience strain. Strive to extend the amount of time you can hold this jaw position before you feel strain. After this exercise drop your jaw and exhale forcefully to relax your jaw muscles.

The Pencil Trick Routine

The Pencil Trick Routine has been recommended by many brass teachers since Reinhardt first wrote of it in 1942. Using a standard, unsharpened wooden pencil, form your embouchure as if to buzz while saturated with saliva. Place the tip of either end of the pencil just between your compressed lips at the point of where your embouchure aperture forms during normal playing, never between your teeth. Using the compression of the lips alone, hold the pencil straight out for as long as possible without strain, usually only a few seconds at first. Gradually extend the amount of time you can hold the pencil straight out before dropping. Similar to the Jaw Retention Drill, following this exercise you should drop your jaw, open your mouth, and exhale forcefully to relax.

Support the weight of your instrument properly

Assuming that a brass player plays right handed, that is, he or she fingers the valves or moves the slide with the right hand, all the support of the instrument should be with the left arm. Holding the instrument properly in such a way that the left hand supports the instrument's weight allows the right hand to manipulate the valves or slide most efficiently. The left hand or arm, depending on the brass instrument, should hold the mouthpiece against the lips securely and is responsible for the pivot.

Spider Web Warm-Up

Reinhardt developed hundreds of exercises he assigned to his students with a number of different variations, but one of the most useful is his Spider Web Routine. Although there are many variations on this exercise, the basic routine begins on a middle concert B flat for all brass instruments (middle C for trumpet, F in the staff for French horn). All pitches given are whole notes at about 60 beats per minute. Following Reinhardt's instructions for lubrication, mouthpiece placement, and inhalation, play a middle B flat at a mp dynamic. Hold this pitch for four counts while crescendoing slightly and ascend up a half step to a concert B natural. Hold this second pitch out to the fullest extent of your playing breath and then repeat. Remove the mouthpiece and rest briefly and then repeat but instead decrescendo slightly and descend a half step to a concert A. Repeat and remove the mouthpiece. Expand the intervals by half steps until you are ascending and descending a full octave. As the interval increases the dynamic contrast should increase for the second pitch. Rest periods between these sets should also increase as the range increases.

Some Advice for French Horn, Euphonium/Baritone Horn, and Tuba

In some ways students of these instruments are at a distinct disadvantage with the Pivot System, although the same basic principles of the Pivot System apply for all brass instruments. What puts musicians performing on these instruments at a disadvantage is that these players, sometimes out of necessity, often rest the weight of the instrument on their leg or the chair. This often sets the horn angle or mouthpiece placement incorrectly for the player's physical type. Utilizing one of the many available instrument stands or even a pillow can help the student get the mouthpiece at the correct height, but often the horn angle is too straight out if the player's embouchure type utilizes a receded jaw. When the instrument's weight is supported on the leg or chair the pivot must be produced by movement of the head or torso, instead of the hand or arms. This can cause difficulties through impeded air support.

While each case must be analyzed according to the individual's physique, it is helpful for horn players, euphonium players, and tubists to practice Pivot System materials standing and fully supporting the weight of the instrument with their hands and arms. If the student is very small or does not have the required strength to do this for long periods of time he or she should practice in this way for as long as possible without strain. Gradually adjust holding the instrument similarly while seated to support the instrument's weight.

When possible, it may be quite valuable to practice Pivot System materials on a second instrument. French horn players can practice on a mellophone, euphonium players on a valve or slide trombone. These instruments will allow the student to experience the sensation of playing without needing to concern themselves with supporting the instrument's weight properly and can then more easily transfer these sensations to their primary instrument.

Never work on more than two correctional procedures at once

Because the most common criticism of the Pivot System is its complexity, this last advice cannot be overemphasized and has therefore been repeated several times throughout this article. A common fault with players and teachers who are inexperienced with the Pivot System is to try to correct too much at once. Playing procedures covered in the Pivot System are designed to be used for practice purposes only, and even then concentration is only on one or two mechanical corrections at once. Once an exercise for a specific correction is completed students of the Pivot System are instructed to forget all about that procedure and work on something else. In rehearsals and performances all the musician's attention should be on playing well, not on technique.

Students prone to "paralysis by analysis" do not understand this vital point. The average person can only effectively concentrate on one or two things at once, and when performing and rehearsing full attention should be given on the music, not the technique. With proper focus on one or two mechanical points, such as the pivot, tongue position, or breathing, the correct technique will begin to become incorporated into normal playing without any conscious effort on the part of the student. If at any point a mechanical correction or a particular exercise appears to be doing more harm than good the student should stop working on it altogether. At a later developmental stage that technique can be addressed again, if it is deemed necessary, but forcing yourself to continue to work on something that is causing problems will not improve your playing.

Conclusion

Dr. Donald S. Reinhardt was fond of saying, "There are as many systems as there are people." (Everett, 2000, p. 2). Any pedagogical approach that takes individual physical and mental differences into account is impossible to summarize. Another expression Reinhardt was fond of saying was, "One man's meat is another man's poison." Attempting to conform every individual brass student into one single approach will have its successes, but will also have many failures. In many cases the fault lies not in the student, but in the teacher's insistence on conforming to what he or she thinks is correct. Many teachers instruct their students according to how they play instead of considering that some of their advice may actually be the exact opposite of how their student will play best. Unfortunately, this is still all too common today.

As information about the Pivot System and other similar approaches becomes more available it will become harder for such teachers to continue their "cookie cutter"approach to brass instruction. With the development of organizations such as the Dr. Donald S. Reinhardt Foundation, dedicated to preserving the teaching legacy of Reinhardt and his Pivot System, more brass students, performers, and teachers will have access to the pedagogical genius of Dr. Reinhardt.

The author would like to thank the following people for their assistance with the development of this article. Eli Dimeff, Paul Garrett, William Gibson, Chris LaBarbera, Tom LeMay, Dave Sheetz, and Rich Willey all helped by contributing materials, proofing the accuracy of the article's information, and answered many questions concerning Dr. Reinhardt and the Pivot System. Without their help this article would not have been possible.

Selected Bibliography

Elliott, D. (1998). Ten questions with Doug Elliott, The Online Trombone Journal. [Online] Available

Everett, T. (1974). An Interview with Dr. Donald S. Reinhardt, The Brass World, Vol. 9, No. 2, 93-97.

Farkas, P. (1962). The Art of Brass Playing. Bloomington, IN: Brass Publications.

Farkas, P. (1970). A Photographic Study of 40 Virtuoso Horn Players' Embouchures. Bloomington, IN: Wind Music Inc.

Froelich, J. (1990). The mouthpiece forces used during trombone performances, The International Trombone Association Journal, 18, 16-23.

Reinhardt, D. S. (1973). The Encyclopedia of the Pivot System of the pivot system for all cupped mouthpiece brass instruments, a scientific text. New York: Charles Colin.

Reinhardt, D. S. (1942). Pivot System for Trombone, A Complete Manual With Studies. Bryn Mawr, PA: Elkan-Vogel, Inc.

Reinhardt, D. S. (1942). Pivot System for Trumpet, A Complete Manual With Studies. Bryn Mawr, PA: Elkan-Vogel, Inc.

Sheetz, David H. Gone But Still Important. [Online] Not Available

Sheetz, David H. Quirks of the Type. [Online] Not Available

Wilken, D. (2000). The correlation between Doug Elliott's embouchure types and playing and selected physical characteristics among trombonists. D.A. diss., Ball State University.