Practice Mutes for Tenor Trombone - A Comparative Analysis

After reading conflicting discussions of the benefits and qualities of practice mutes, I decided to make a rigorous evaluation of practice mutes for tenor trombone. I already owned three practice mutes, and by borrowing one (the Denis Wick mute) from a friend, and purchasing another (the highly regarded Wallace mute), I could test a representative sampling of five well-known trombone practice mutes. From the least to the most expensive, they are:

- Humes and Berg, Sh Sh Quiet, Mannie Klein practice mute (street price $18)

- Softone mute for 7" to 8" bell (street price $30)

- Denis Wick practice mute (street price $45)

- Wallace practice mute (street price $50)

- Yamaha Silent Brass (street price $220, $95 without electronics)

H& B Klein |

Softone |

Wick |

| |

|

| Wallace |

Yamaha |

Tests Performed

Tests included sound attenuation, intonation (pitch accuracy), resistance, weight and balance measurements, and design evaluation. The design of each mute was evaluated for safety, security, materials, and convenience. The most important of these parameters is safety. If a mute can cause harm to the instrument or player, it should not be used. The harm could be physical, such as scarring of the bell, or mental, by promoting inaccurate playing. Summary of the test results is made in a chart rating the performance of each mute in each of the categories except resistance. Finally, recommendations are made based on the requirements of the player.

Temperature and relative humidity can have an effect on the response of a horn. Fortunately, the room used for testing is always air-conditioned, with a temperature hovering around 75° F., and a relative humidity of around 40%.

During the tests, I confirmed that it is possible for a practice mute to have benefits beyond just providing sound attenuation. At least one improves pitch centering, and therefore has a positive effect on the tone of the instrument. Some may even have detrimental effects, apparently caused by inaccurate feedback to the player. In these tests, it was not found necessary to play loudly in order to obtain some of the benefits of the better practice mutes, though there are some methods which use loud playing to enhance opening of the throat. For the best results, regardless of the method, there are two basic requirements:

- The mute must be fairly accurate. If it has an uneven response in either loudness or pitch, the player may make inaccurate corrections, which will carry over into playing with the open horn.

- The sonic feedback must be adequate for the environment. If the mute attenuates the sound too much for the surrounding conditions, the player may not receive adequate pitch or volume information.

Some people use practice mutes strictly to make the horn quieter. But, I would like to re-define the term "practice mute" as "a mute that provides the user some positive benefits to enhance the practice session."

Using this definition, it is possible to expand the possible uses of practice mutes to include not only sound reduction, but enhancement of proper breath control, pitch control, tonal enrichment, and, as with the electronics of the Yamaha Silent Brass system, to duplicate the effects of various sonic environments.

A practice mute may be useful in various situations. Backstage warm-ups can proceed without disturbing others. The mute may help the warm-up to proceed more quickly and effectively. The Yamaha Silent Brass mute might be used to make demo tapes, though there is a fair amount of hiss in the electronics, and the Softone mute doubles as an excellent bucket mute.

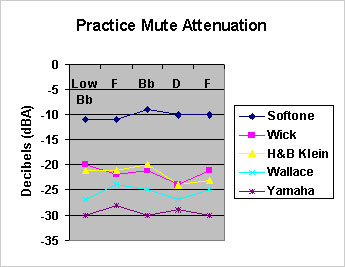

Attenuation Tests

For these tests, I used a Radio Shack Sound Level Meter, Catalog No. 33-2050. It was set for slow response, and measured the sound intensity in decibels on the "A" weighted scale. The "A" weighting closely approximates the sensitivity of the human ear to various frequencies. The microphone end of the meter was located approximately two feet from the bell of the horn to keep the meter out of any reflection waves at or near the bell and still be close enough to reduce the effect of room reflections.

The trombone used for these tests was a Bach 16. Only first position notes were tested, from low Bb to F above the staff. This was to ensure maximum repeatability. Each note was first played with the open horn several times at a comfortable medium volume. The peak measurements were averaged and written down. Then, the practice mute was attached, and the same note was played again several times, with an attempt to duplicate the feeling of the note played with the open horn. The attenuated sound level, in decibels, was subtracted from the open horn sound level to arrive at an approximate attenuation value, here expressed as a negative value. For example, if the open horn sounded 90 decibels, and the muted horn averaged 70 decibels, the charted value is -20 (minus 20) decibels. Relating these numbers to perceived differences in loudness is complicated. However, an increase of 10 decibels is approximately equal to doubling the perceived loudness. Take these results as indications, remembering that we are measuring not only a mute but also an entire system of sound production, consisting of player, mouthpiece, horn, and mute. Readers interested in more information on the relationship between sound level readings and perceived loudness are encouraged to follow the link in my third reference at the end of this article.

It was expected that this test would be imprecise. Trying to match the open horn input volume with that of the muted horn is difficult at best. However, the test was conducted several times, and the results were fairly repeatable.

|

|

Chart 1. Practice Mute Attenuation.

|

The original Softone mute came with a number of foam ring inserts, and was tested with the outer foam rings in the mute. This was necessary to achieve maximum attenuation with this mute, and the rings help the mute seal better against the back of the bell. Addition of the rest of the foam in the center of the mute had no further effect on attenuation. At this time, it is understood that the foam insert rings are no longer provided with this mute. The user can easily make foam inserts, however, and instructions for doing so are included in this report. Without the rings, attenuation was reduced by nearly 5 decibels. 10 decibels of attenuation would be adequate for many situations, but would be still too loud for use in a quiet apartment setting late at night, for example. However, this mute provides the most accurate feedback, and seems to demand fairly accurate pitch centering, which is beneficial.

The Yamaha mute was tested without its electronics, because with the electronics volume can be varied to the earphones. Without the electronics, attenuation is nearly 30 dBA (this measurement corresponds with Yamaha's specifications). The resulting loudness level may be insufficient to compete with ambient sound in some situations. It may become necessary to use the electronics with this mute to hear anything at all.

Note that the other insertion type mutes have more "bumpy" attenuation plots than the Softone or the Yamaha. It is believed that the spikes are related to internal resonance, which either reinforces or cancels certain frequencies. The Wallace mute had clearly audible resonance frequencies, which could be easily detected by singing into the open end of the mute (like singing into a bottle). They may have caused the loss of attenuation at middle F and its octave. These effects with the Wallace mute can be easily improved, however (see the section on pitch accuracy). The Yamaha mute had detectable resonance as well, but the greater attenuation of the mute reduced its effect. Therefore, the Softone mute, with the least attenuation, and the Yamaha mute, with the most, provide the most accurate volume feedback to the player (provided that the Yamaha mute can be heard).

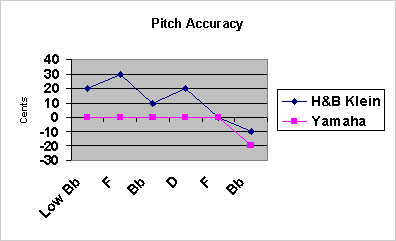

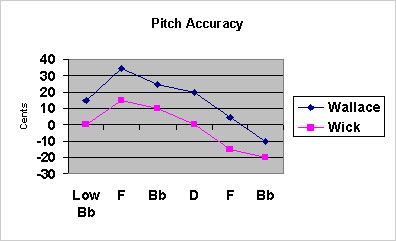

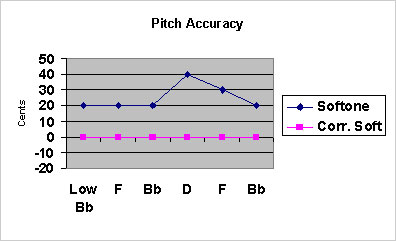

Tests For Pitch Accuracy

For these tests, a Korg Auto Tuner, Model AT-1, was used, calibrated to A=440. The trombone used for these tests was a Lawler .500 bore model with 8" bell, large taper. This horn is exceptionally in tune. After careful adjustment of the tuning slide, it is easily possible to play first position low Bb, F, Bb, D, F and high Bb, all within 5 cents of accurate pitch, without adjustment of the hand slide.

Only the above first position notes were tested for accuracy, because of the possibility of inaccuracies being introduced by the extension of the hand slide.

To make it easier to read the results, three separate charts are used. One shows the results for the H&B Klein mute and the Yamaha Silent Brass mute (again without the electronics). The next shows the Denis Wick and the Wallace practice mutes. The last shows the Softone mute, with tuning uncorrected and corrected.

|

Chart 2. Pitch Accuracy of Klein and Yamaha Mutes. |

|

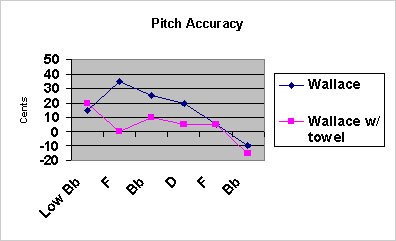

Chart 3. Pitch Accuracy of Wallace and Wick Mutes. |

|

Chart 4. Pitch Accuracy of Softone Mute (Uncorrected and Corrected). |

What chart number four shows is that the Softone mute, without correction, was always at least 20 cents sharp, and had a peak of 40 cents sharp at D, returning to 20 cents sharp at high Bb. Another trombone player who has a Softone mute had also reported the sharp D to me. By pulling out the tuning slide approximately 3/8 of an inch, not only were the notes that had been 20 cents sharp in tune, but also the peak at D disappeared entirely. The Softone mute, thus corrected, was completely in tune with the open horn, matching it note for note.

Notice in the chart of the Wick and Wallace mutes that the two plots are essentially parallel. By making a slight correction to the tuning of the horn, as with the Softone mute, the Wallace mute plot would be almost identical to that of the Wick mute.

The H&B Klein mute was similar to the Wick and Wallace mutes, but was closer to being accurate at middle Bb. The Yamaha mute, like the Softone, was virtually in-tune, and the dip at the upper Bb may have been at least partly due to difficulty in getting the tuning meter to respond to the extremely low volume of sound from this mute.

After making the initial tests, I found that the Wallace mute could be improved cheaply and easily by inserting a sheet of soft paper towel into the mute to reduce internal reflections. The towel was just stuffed in so that it filled about half the interior volume, leaving the center tube open. Here are the before and after test results.

|

Chart 5. Pitch Accuracy of Wallce Mute With and Without Towel. |

With the addition of the paper towel stuffing, the attenuation of the Wallace mute also increased to an average of 29 dBA, nearly the same as that of the Yamaha mute. Because of the Wallace's brighter sound, however, it is easier for the player to hear.

The Softone and the Yamaha mutes provided the most pitch accuracy. The "corrected" Wallace mute is fairly accurate in the middle registers.

Tests for Resistance

Much has been said about the resistance of practice mutes, even by some of the manufacturers, as if resistance is necessarily bad. Here are two examples:

"Free easy blowing. No Resistance in all registers." From a Humes & Berg brochure describing the Manny Klein Sh Sh Quiet Practice Mute."...it has none of the stuffy restricted feeling of conventional practice mutes." From a Yamaha Silent Brass ad.

In an ITA Journal article, Denis Wick claims that students using his practice mute for loud practice were aided in playing with open throats by the extra resistance of the mute.

Is resistance good or bad? How much is too much, or too little? I'll let you decide. Here are some facts.

First, there is always some backpressure created when playing a brass instrument. The amount will vary with the design, length of tubing (as when extending the slide), diameter, bends, added restrictions, such as valves, and with the incident pressure created by the player.

Second, insertion or attachment of any device that partially obstructs or disturbs air pressure will increase backpressure (resistance). Any valve, tubing, or mute added to the system will add to the total system backpressure. For a practice mute to work at all, it must create some added backpressure (resistance).

Third, without some backpressure, the sound producing system will not work. Sound is pressure waves in air. Elimination of all backpressure would only result from elimination of incident air pressure, or by eliminating the air, itself. To do this while trying to make a sound would mean that the player would be playing in a vacuum, which obviously won't work. Conversely, added resistance can reduce the flow of air eventually to the point of eliminating sound.

Clearly, the player will most likely feel added resistance when any practice, or other type of mute is added to the system. So, let's compare the resistance of the mutes under examination, for whatever value the information may have on your selection.

To do this comparison, I connected a plastic piping tee, via the straight through branch, with 7/8" plastic tubing, to the mouthpiece receiver of the Bach 16 trombone. The branch of the tee was connected by another, smaller tube to the top of a simple device which uses a rising ping-pong ball to indicate air pressure. By using the rising ball as an indicator, I could deduce the relative resistance of the practice mutes. One by one the mutes were securely inserted into the bell of the horn, and the pressure to lift the ball was tested with this device. The easier it was to raise the ball, the greater the backpressure or resistance of the mute. Additionally, to confirm my results, I blew directly into the inlets of the insertion type mutes. Obviously, the Softone mute could not be re-tested in this manner. Specific values are not given, but remember that backpressure will increase with inlet pressure. From the most to the least resistant they are:

- Yamaha Silent Brass

- Denis Wick

- H&B Klein

- Wallace

- Softone

It was difficult to rank the last two. It seemed that the Wallace was slightly less resistant than the Softone in loud playing situations, but that the Softone seemed less resistant at moderate volumes. All the mutes have perceivable resistance.

As previously mentioned, Denis Wick claims that playing loud, low notes into his brand of practice mute aided students in learning to play with an open throat. The author tried the exercise with each of these mutes and concluded that it would work equally well with any of them. The author has also noticed that loud playing with the open horn increases efficiency, as well, at least temporarily. The added backpressure of the practice mutes may help speed up the beneficial effects of loud playing, but added backpressure from a mute is not a requisite to achieving them.

Weight and Balance Measurements

Weight and balance are important, probably much more so than backpressure. If too much weight is added to the bell of the horn it can cause fatigue to the supporting hand. Think of the added weight as a lever force offsetting the balance of the horn. A little added force at the end of this lever arm can be likened to a torque wrench being applied to the player's wrist. It doesn't take much added force to require a considerable counterbalancing force on the part of the player.

Weights were measured in grams on a precision laboratory balance (Ohaus triple beam), and rounded to the nearest 1/2 gr. I've also converted the weights to ounces. From the lightest to the heaviest the weights are:

| Mute | Grams | Ounces |

| Softone (without outer rings) | 85.5 | 3.02 |

| Softone (with outer rings) | 101 | 3.56 |

| Wallace | 136.5 | 4.81 |

| H & B Klein | 163 | 5.75 |

| Wick | 171 | 6.03 |

| Yamaha | 228 | 8.04 |

Weight, by itself, is only part of the balance picture. The distance from the approximate balance point of the horn to the place where the weight is applied is known as the moment arm. The weight will apply downward force at the end of this moment arm. The effect of gravity will be greatest when the moment arm is level, so for our comparison we will assume a level horn. The length of the moment arm is not determined by how far the entire mute sticks out beyond the bell of the horn, but by how far the mute's center of gravity is from the end of the bell. By carefully holding each mute between thumb and forefinger, one can find the approximate location of the pivot point where the mute is in balance. The pivot point is opposite the center of gravity of the mute, which is along the center axis. I located the balance pivot points for each of the mutes and marked them with little squares of tape. Here are pictures of the mutes, showing the center of gravity marks, in (or, in the case of the Softone mute, over) the bell of the Bach 16:

Wick |

H & B Klein |

Softone |

Yamaha |

Wallace |

|

As you can see, the center of gravity of the Wallace mute is only about 1/8" from the edge of the bell, but the center of gravity of the Yamaha mute is about 1-1/2" from the end of the bell. Even if the two mutes weighed exactly the same, the Yamaha mute would produce the greatest downward force because of its longer moment arm.

I used the distance from the center of gravity mark to the first brace of the bell, which is a fair approximation of the pivot point, as my lever arm distance. Multiplying this distance by the weight of the mute gives me the approximate downward force, or mechanical advantage, of each mute on a level horn. The values are expressed in foot-pounds. These values will vary with the design and size of the horn. Larger bells will allow the insertion type mutes to seat closer to the pivot point, shortening the moment arms, and will reduce their downward mechanical forces. The numbers for the Bach 16 are presented here for comparison:

| Mute | Foot-pounds |

| Softone | .27 |

| Wallace | .32 |

| H & B Klein | .39 |

| Wick | .41 |

| Yamaha | .59 |

The effect of each mute on the balance of the horn is now clear. Of course, we continually alter the balance of a trombone as we move the slide. But these changes are temporary. An excessive steady imbalance can cause fatigue.

As the weights alone seemed to indicate, the Softone mute has the least effect on the balance of the instrument, and the Yamaha the most. With nearly six tenths of a foot-pound of downward mechanical force, the Yamaha mute should probably be counterbalanced if it is to be used for long periods of time.

Design Evaluations

The most important design consideration is safety. If a practice mute could cause harm to the player or to the instrument, it should not be used. The above issue of imbalance is also a safety issue. Tendon or muscle damage can be caused by constant straining to balance an instrument.

One of these mutes, as delivered, can cause physical damage to the horn. Another is insecure, and tends to fall out of the horn. These two will be discussed first.

Wick

The Denis Wick practice mute appears to be an adaptation of a straight mute. The body is aluminum, and tends to dent when dropped. Instead of three or four longitudinal corks for support, a full encircling cork is used, and there are two 1/4" holes drilled in the wide part of the mute body, just above the seam. No filling or baffling is used inside the mute. The cork diameter at the top is 1.55" and provides a fairly secure fit.

Notice that the top of the cork is mounted approximately 1" below the throat of the mute. This leaves an exposed metal edge that can scratch the bell of the horn. Physical damage can happen with any but the most careful insertion of the mute, and it can happen if the mute loosens and falls out of the bell.

The problem can be avoided if cork or other cushioning material is glued along the rim of the mute, so that the metal edge cannot come in contact with the horn. The cork or other protective material should be thinner than the existing cork ring, so that the mute seats normally. Cut out a piece of paper to fit all around the mute inlet, first, to use as a guide for cutting the cork or other protective material. The protective material should be glued on with contact cement for security. Simply taping the edge of the mute inlet is not a sufficient cure for this problem.

If you own, or plan to buy, one of these mutes, I strongly advise you to make this modification. I encourage the manufacturer of this mute to take steps to remedy this admittedly common design flaw.

Yamaha

The Yamaha Silent Brass mute is made of a sturdy molded plastic, and is resistant to dents. Air escapes the mute from a narrow channel along the seam between the top and bottom parts of the mute body. The top of the mute has a rubber ring, instead of cork.

The width of the top of the rubber is 1.99" and only the leading edge contacts the bell of the trombones used in this test. As demonstrated in the section on weight and balance, the large throat diameter causes the center of gravity of this mute to extend well beyond the bell with a typical small or medium bore horn. It will fit better in a bass trombone, or a large tenor bell.

The rubber seal tends to crack with age and use. This was observed with my Yamaha mute, and with another one owned by a colleague. As condensate builds up inside the bell of the horn, it works into the surface cracks of the rubber. This lubricates the rubber at the gripping surface, and the mute works loose. As a result, the Yamaha Silent Brass practice mute has a tendency to fall from the horn.

If this mute falls while attached to the electronics, wires may be pulled, and possibly damaged. The wires may also redirect the fall in such a way that the mute could come in contact with other objects and cause damage. At the very least, a sudden loss of attenuation and resistance can result in a loud blast from the horn, right when quiet is needed.

Changing the material at the mute inlet from rubber to cork may help to reduce the hazard from falls, but the real problem is with the throat diameter of the body. At the throat there is a large support assembly that holds one end of a threaded rod, presumably there to hold the electronics of the mute in place. This support assembly blocks a considerable part of the inlet open area. If this support assembly were redesigned to take up less inlet area, then the throat diameter could probably be reduced. The mute would then fit deeper into the bell, improving the balance and security of the mute. However, such modifications are not within the capability of the average user, and would probably require costly retooling by the manufacturer. Still, the concept of the mute is a good one, and I encourage the manufacturer to revisit the design of this mute. Meanwhile, because of its poor balance, and tendency to fall from the horn, this mute is not recommended for use with most small or medium bore trombones, except where the electronics are needed for special uses. Even then, caution is advised.

H&B Klein

The Klein practice mute is made of some kind of coated fiberboard material that is very tough. It is riveted along a longitudinal seam, and resists dents very effectively. The base is 4" in diameter, and the mute is 10-1/2" long. The cork is properly located at the inlet edge. Diameter of the cork at the leading edge is 1.54" and it fits deeply and securely in the bell. Any insertion type mute can potentially work loose and fall from the horn, but this one is less likely to do so than the Yamaha.

Inside the mute there is a center tube that leads to a bottom chamber filled with some kind of baffling. Air passes through the central tube, and exits through a 1" hole in the bottom of the mute. This hole is screened with some kind of cloth that holds the baffling in place. No attempt was made to estimate the effective open area of the mute.

The H&B Manny Klein practice mute is well made and sturdy, and has no obvious design flaws that could cause harm to the instrument.

Wallace

The Wallace practice mute is made of a fiberboard material, covered with a hard red colored material. It has a compressible plastic material at the mouth, instead of cork. This material has a dimpled surface, presumably to help the mute grip the inside of the bell. The mute is only 6-5/8" long, compared to 10-1/2" for the H&B Klein. The base is 1-1/4" wider than the base of the Klein, so the mute has a more tapered cone shape. The outside diameter at the throat is 1.7" but because this mute is short, the seating area is tapered more than those of the other mutes. For this reason, it tends to grip over a larger part of its surface. This fact, along with the light weight and close-in center of gravity, makes for a fairly secure attachment, with little tendency to fall.

Inside the mute is a 7/16" inside diameter plastic tube, which runs from about halfway down the length of the mute to the exit at the bottom. There is no baffling or other material inside the mute. Based on my experiment with a piece of paper towel, the addition of some baffling material will increase attenuation and will improve pitch accuracy in the midrange. If you own a Wallace practice mute, you should do your own experiments with adding baffling material. Because of its design, the Wallace mute is the only one of these mutes that is easy to modify in this way, and the modification is easily reversible.

The Wallace mute appears to be well made and sturdy. Because of its small size, and light weight, the Wallace mute is easily the most convenient to carry of the insertion type mutes. There are no obvious design flaws that could pose a hazard to the instrument.

Softone

The Softone mute is made of neoprene rubber, and it slips over the bell. There are no hard materials that could cause harm to the instrument. It is the only mute in this review that cannot fall from the bell when used as a practice mute. When used as a bucket mute, it is draped partly over the bell, and in this configuration could fall, but the fall would be inconsequential. The material is so light and soft that it would do no harm. The mute is sewn together as three pieces; front, side and back. The side piece is about 3" wide. Air exits from eight 1/8" diameter holes punched along the circumference of the side piece. The mute comes in different sizes for different diameter bells.

The manufacturer states that to use this mute as a practice mute, the player should first blow a puff of air, like blowing up a balloon, to seal the mute against the back of the bell. The author had difficulty maintaining this seal when using it without the foam rings, previously mentioned.

Unfortunately, the manufacturer has discontinued supplying the foam rings, but you can easily make them, yourself. Most hardware stores carry foam rubber. Get either 1/2" or 1" thick foam rubber and cut it into 4 (four) 1/2" thick rings, or 2 (two) 1" thick rings. Below is a photograph of some foam rings and the tools the author used to make them.

A cutting guide ring is first cut out of cardboard. The outside of the guide ring should be approximately the same as the inside diameter of the mute. The inside diameter of the guide ring should be about 1-1/4" less than the outside diameter.

Cut one thickness of foam at a time using a utility knife. The edges do not need to be perfect. Then, insert the foam rings inside the mute. They will keep the front of the mute away from the bell, and help to seal the back of the mute. It is still recommended to use a strong initial puff of air to seat the mute. As mentioned, these rings also improve attenuation.

While the manufacturer is encouraged to offer the rings, at least as an optional accessory, the Softone mute is well made and designed. It is by far the most convenient of these practice mutes to carry. It can even be used to protect the bell of the horn in transit. The materials are durable, and there are no design flaws that could cause harm to the instrument.

Summary

Readers should use the above information to form their own conclusions. Based on the above, I have rated the practice mutes based on their performance in each of the tested categories except resistance, using four levels; Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Recommendations

There is no single perfect practice mute for all purposes in this group. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses.

If you want the most benefit from a practice mute, the Softone mute is an excellent candidate. However, if you need excellent attenuation, the Wallace mute should fit the bill nicely. For maximum practice benefits and attenuation, for less than the cost of the Yamaha mute alone (without electronics), you could have both the Softone and the Wallace mute. This way, you would have two very small, light and portable mutes, one with excellent practice benefits and a second use as a bucket mute, and the other with excellent attenuation for times when you need to be very quiet. Or, if you consider cost to be an important factor, the Softone and Klein would provide a workable combination. You could take the Softone with you anywhere and leave the other mute in your practice room. Read the tests, and draw your own conclusions, keeping in mind that there are also other practice mutes not reviewed in this report that might be worthy of your consideration. You may wish to use this review as a guideline for their evaluation.

References

Greene, Earnest S. (1962). Principles of Physics. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Wick, Denis. (1992). "A Practical Aid to a Beautiful Sound." ITA Journal. Spring 1992. Vol. 20 No. 2. p. 36.

Truax, Barry. (1999). Handbook for Acoustic Ecology. Originally published by The World Soundscape Project, Simon Fraser University, and Arc Publications, 1978. http://www.sfu.ca/sonic-studio/

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Ira Nepus for the gift of the Softone mute several years ago, and to Russ Lum for loaning me his Denis Wick practice mute for these tests.